Kerry James Marshall: The Histories

Royal Academy of Arts

Until 18 January 2026

Until 18 January 2026

I had planned to visit the Van Gogh / Kiefer before it closed and found by the sheer scale of some of the works that the show was paradoxically smaller than expected – set within three rooms. Many of Kiefer’s mixed media works are interpretations of Van Gogh’s classics without too much reinvention except for scale and are somewhat predictable. In fact, Joan Eardley was more subtle and effective with this collage technique. There was nothing of his inner workings to tell us how he had thought through these concepts, unlike the many sketchbooks of the superb William Kentridge exhibition in 2022, where one felt they could climb inside his mind. We were hit with room sized canvases of straw, paint & sometimes gold leaf, juxtaposed against the post impressionist. I found myself trading the German’s technical impressiveness for his brashness. Its visual impact was unavoidable, but it was sometimes more noise than music and I’m not sure there was much to learn.

However, Vincent’s work as ever remains captivating and I was sucked in to analyse every single mark and dab of oil paint. He was as much a Romanticist as he was an Impressionist.

I was done after about half an hour so I strolled in to see the Kerry James Marshall – and this was a wonder…

It is large and captivating and my eyes and mind were exhausted by the end of it. The show prods but doesn’t preach, educates and engages through posing scenarios and narratives, and for me this is what art should be doing – asking questions as much as giving answers.

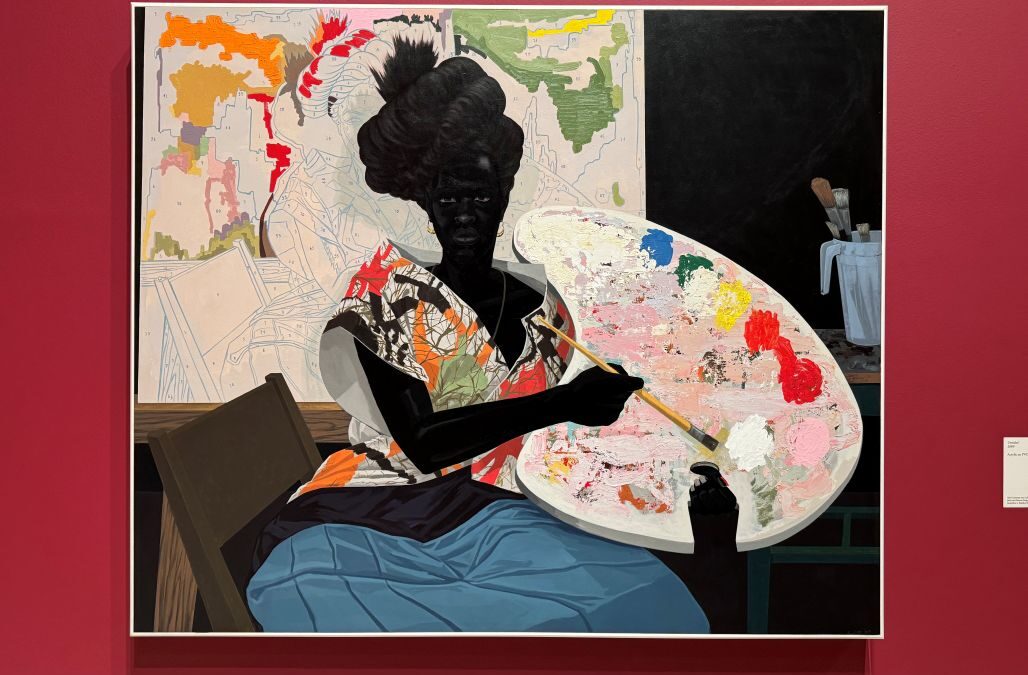

One of the fundamental themes is the subject of (being) “black”. Marshall paints black people as shades of black. This is his symbolic statement about the black person’s visibility or more accurately lack of in society and history – forgotten, overlooked and traded into the darkness. By extension of this, it questions identity, rights, values and where the black person’s position in society is today. One quotation makes reference to whether black people feel comfortable in a predominately white park, with an analogy drawn and a twist on Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte”. References are also made, explicit or otherwise, to Manet including a very humorous take on his “Olympia”.

Anyone with an interest in painting and social commentary will be provoked and stimulated by the many large detailed colour compositions and their strong narratives depicting; the slave trade, housing projects, social relevance, domesticity, people just going about their lives and that word “integration”.

The theme of the “Invisible man” stops you, makes you think and then see. Not because at a personal level, social media can make us feel invisible, but when it is applied to a section of society or a race, then it isn’t about vanity and ego but of a systematic failing in humanity – over centuries.

These paintings have soul and a kind of sound and many feel like stills from a movie which may be the trick. Marshall tells us about the past (and yet the facts never diminish or cease to shock), the present day, but somehow by studying them, one releases the pause button and projects what they may tell us about the future. This is what makes this show of importance.

Is it important to a white person? Yes, because black history and enslavement was not taught in my school and still has a long way to go. This is an Education. It holds both a mirror and a window to the viewer and our challenge is to find the answers.

There is one particular painting in the first room, which depicts a black woman wielding an overly large artist’s palette. Surrounding her is a paint-by-numbers concept which may suggest a do-as-I-say authoritarian (slave trade) state, but is the palette a shield for battle and the fight for freedom? The artist is as much a warrier as they are an artist as they are a satirist.

A must see.

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories

Royal Academy of Arts

Until 18 January 2026

Until 18 January 2026

– Article written by Graham Everitt