Until 15 February 2026

The theory that the power to shock only achieves diminishing returns is usually dispelled when it comes to War – be it the Gaza Strip or Ukraine in current times. And with the exception of the unravelling Slave Trade, nothing shocks like the Holocaust and continues to shock some eighty years on. This section of the exhibition is possibly Lee Miller’s strongest work – WWII was her calling and she probably knew it. Her earlier experiments with light and dark, metamorphosis, intriguing and unsettling surrealism together with Middle East journalistic depictions all merged to enable her to capture the war in Europe in vivid, striking black & white compositions. And if not with sensitivity then with sober candidness.

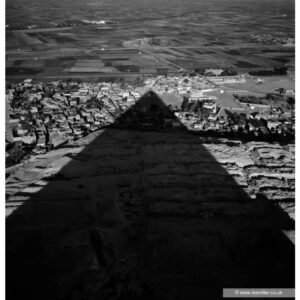

But it would also appear at times that the American was lost for words and yet still resorted to writing notes in order to try and make sense of the brutality and madness of it all – some of these statements suitably complement the show. Paradoxically, her photographs weren’t enough and yet said everything. Even in the horror and calamity of death and destruction she sometimes somehow found beauty; an arc of light, a defining shadow, a gaze. Despite diminishing health and rationing, she refused to return to England until her work was done. Her dedication, skill and spirit were unquestionable. One senses Miller was as much a soldier as she was a photographer. This was exemplified in the biographical movie released in 2024, superbly portrayed by Cate Winslet.

Miller’s early career as a model later connected to her photojournalist work with Vogue during wartime, where the publisher’s modus operandi was to play with irony and promote positive imagery as morale boosters rather than depict the blunt and disturbing bloodshed. This was perhaps most biasedly demonstrated when the magazine’s Editor chose the fashion stylised work of Cecil Beaton over her fly-on-the-wall brutal realism.

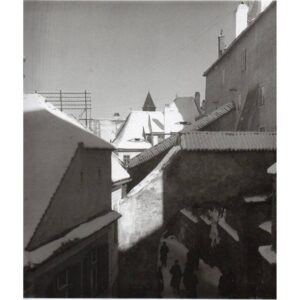

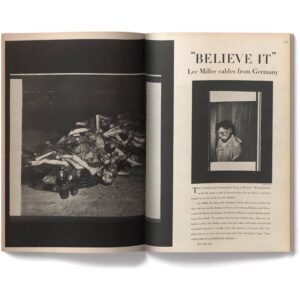

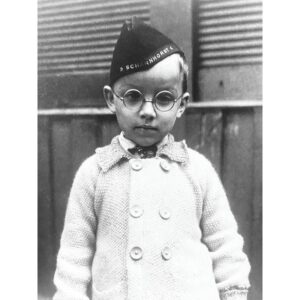

However, Miller seemed fully aware of how the truth can undermine evil. It would occasionally burst out of her work with acerbic vividity such as the pile of dead emaciated bodies (BELIEVE IT, American Vogue 1945) or through the wit but eerie The eyes of Sibiu, Piața Mică, Romania, 1946, which captured dormer windows as prying eyes – possibly expressing the after effects of trauma and surveillance. Her post war condition would most likely be diagnosed as PTSD if assessed today according to many.

Miller was the subject matter in the early years such was her photogenic appearance, but it went beyond the superficiality of the fashion industry. With Man Ray as partner at that time, it allowed her to experiment with surrealist and androgynous imagery (one can see how Bowie and many others were later influenced), together with the human form which the likes of Henry Moore would pursue in sculpture. Miller was in good company; Max Ernst, Dora Maar, Dylan Thomas, Charlie Chaplin and Picasso to name but a few, which must have inspired and who were all gracefully captured in her portrait work.

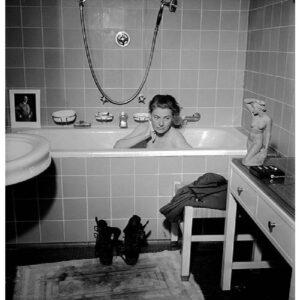

Fundamentally, this was a woman in a man’s world – be it art or war. The Beaton anecdote was probably not lost on all readers, demonstrating she was also and always fighting her own war of being taken seriously as an artist; a photographer; but ultimately a Woman and not a second rate citizen. It’s not far off 100 years since Miller plied her trade and even now this would be a challenge. However, the necessary upgrade in female recruitment during WWII correlated with Miller’s own rise, and perhaps the usage of the name “Lee” was her canny way of progressing through the media world. The portraits of the black opera singers in 1933 is the work of someone who wanted to break boundaries, conventions and stereotypes, because they needed breaking if the world was to change from the likes of Hitler. And perhaps one the greatest examples of dark satire were the self portraits of herself and David Scherman sitting in the Führer’s bathtub (1945) – a mocking slap in the face of evil and reclamation of peace.

Some of the imagery could be of today. The bandage wrapped form almost smiling in hideous pain (Bad burns case, 1944) is something we see on our own news screens. War never changes, only the people who start it do.

Experimentation, purist photography (From the top of the Great Pyramid, Giza, 1938) or spine chilling journalistic imagery – Lee Miller was a master of the camera. It is a large and absorbing exhibition – 2 hours went by without realising. Go and see if you are in the Smoke.

Lee Miller at Tate Britain

Until 15 February 2026

You can watch the documentary Lee Miller: A Life on the Front Line on BBC iPlayer, by clicking the link below.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000hy2p/lee-miller-a-life-on-the-front-line

– Article written by Graham Everitt

Thanks for a superb article.